Comments?

For the basics, see

- Website & Privacy Policies

- How To Get Involved

- The Role of the Park

Search options:

Department Site Map

Custodians:

How The First Oven Got Built

How The First Oven Got Built

How The First Oven Got Built (1995)

How the idea started

The sight of a crumbling village oven, in a documentary film about Portugal, started our bread oven idea here at Dufferin Grove Park. The film showed the village priest encouraging the people to repair their old communal oven, and then there was a short clip of some village women baking at the rebuilt oven, their faces lit up by the fire. When we described this movie scene to people at the park, their faces lit up too. Over the following weeks we were astonished at the strength of people's reaction to the oven story, as we were asked to tell it again and again. Of all the ideas ever proposed for the park, there had never been such a uniformly enthusiastic response. There must be an old memory (of bread baked on the hearth with fire) that people don't seem to have let go of, even after half a century or more of sliced bread in plastic bags.

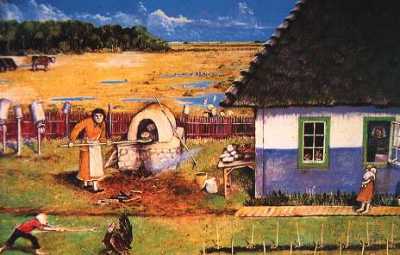

Bread ovens were very common in 19th century and early 20th century Canada. For example, here is a painting by William Kurelek, of a prairie farmstead:

A Prairie Farmstead

William Kurelek

In Quebec it's not hard to find outdoor ovens still standing, although many of them are crumbling now and need repair. When we decided we wanted to build an oven, we asked around and wrote to people, but we didn't really come up with a good plan until we heard about Alan Scott. We got in touch with him and asked him to send us his oven plans for a mid-sized (4x6 foot) hearth. Alan put us in touch with a masonry-heater builder in Quebec, named Norbert Senf, and we arranged that a neighbourhood contractor and friend of the park, Nigel Dean, would build the base, Norbert would come and build the working parts -- the hearth and the dome -- and then Nigel's crew would finish the job. Since then, Nigel has built a number of public ovens himself in other Toronto locations, and other oven-builders have established themselves as well.

Picture Gallery: How the oven was built

Here's how our first oven was built:

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

Tips: What to do when you have the money to get started

Stake-outs

Assuming you have settled the spot where the oven will stand, call the utility companies (telephone, hydro, gas, water) to arrange for a stake-out of the site. This is because the oven needs a foundation of gravel, about 15 inches deep, and when anyone digs a hole in a city they have to know for certain that they won't hit any wires or pipes. When the stake-out people come they will give you some maps of your site with any possible pipes/ wires marked and an official "clearance" number. Keep these papers in your file. You must get moving on your construction soon after the clearances because in many places they expire in a month.

Workers

While you wait for the stake-out, look around for your builders. We used:

- two labourers to dig a 15-inch-deep hole about four inches wider and longer than the oven platform's "footprint" and fill it level with gravel;

- two skilled workers to make a level platform of reinforced concrete on top of the gravel surface;

- a bricklayer to lay a box of concrete block, nice and level, up to almost waist height (usually four blocks high);

- a skilled worker back again to put a level platform of reinforced concrete on the second layer;

- a skilled bricklayer to build the hearth, the dome, the brick housing, the chimney, and mortar in the oven door (in other words, the oven's working parts);

- a carpenter to build a roof in such a way that the empty spaces under the roof can be packed with fire-proof insulation;

- it was very nice for us to have a few handy, interested enthusiasts from the neighbourhood to be the helpers for these skilled workers.

Not everyone makes a good helper -- a cautionary tale. A youth "gang" called the "L.A.'s" used to hang around a park near ours, around the time when we were ready to build our first outdoor oven. Five of the more ambitious (or broke) gangsters had some work with us at Dufferin Grove Park from time to time, digging flower beds and helping Isabel with the cooking fire. We thought we should hire them as labourers to work with Nigel Dean, our oven contractor -- we'd provide good work experience for these fellows and at the same time we'd get some extra help for our oven project. The city had given us a small grant meant for rescuing troubled youth, and so for $10 an hour we set these young fellows to digging the foundation hole and filling in the gravel. Then Nigel, the contractor, got them to help him start building the oven. The more tricky the work got, the more our five workers rebelled at taking orders. Nigel was actually a pretty cool guy, a drummer in a band when he wasn't a contractor, and he was a cheerful boss, but he knew what had to be done and how to do it, and our workers didn't want to go along. They wanted to dream out loud about how they intended to set up as independent contractors right after they finished this job. They wanted to have lots of smoke breaks. They wanted to argue with Nigel about what should be done next. They wanted to rest when the cement was freshly made in the mixer and ready to pour. When Nigel insisted that they come and help him NOW, they threatened to beat him up. That was, of course, the end of their career with us.

About using volunteers: When we built our first oven, we thought we might get help from some of the retired Calabrian men who played cards at the park every day. Several of them were experienced bricklayers. The first thing we found out was that none of the old men had the slightest intention of giving their labour for free, and most of them weren't interested in building the oven for money either. The point of retirement was that their days of labouring were over, and finally they could play cards and talk or shout all afternoon, every day of the week. That kind of paradise did not include temporarily going back to their former trade. Those few who were willing to work for money couldn't speak English and we couldn't find out about their credentials. (Their friends implied that they might not be very competent, a conviction that seemed to be mutual among many of these old card cronies.)

About city or union labour rules

In the end it seemed that the best thing was to hire an active contractor, whose work was known to some of us, who lived in the neighbourhood and was interested in our small project. He sub-contracted the bricklayer and did the rest of the work himself. After we fired the gangsters, we got him one young assistant (a local youth, unemployed at that time but handy and cooperative) as a labourer, whom we also paid.

Before we started building, we had asked for an oven cost quote from the municipal building department. That quote came in at exactly twice the cost of building the oven with our contractor. Every motion of the city workers would have been counted. The contractor had more leeway. Since his labourer was a youth who was learning on the job, an unofficial apprentice, his wages were half those of a city labourer. Also our contractor was a local resident who was committed to the oven project as a good thing for our neighbourhood, so he gave us a bit more time than he charged for. And the final consideration was that the city would have put us at the bottom of a long list of pending projects, whereas our contractor was able to fit us in sooner.

Were we breaking the City of Toronto labour rules? It's hard to say. Our project was small and unusual, so it probably wasn't seen as a precedent for other incursions. The contractor was known to us, committed to the project, and giving us a bit of his time free. This seemed to allow the city workers to consider him as a volunteer rather than an outside hire. The fact that the oven-building was mainly on weekends and evenings, outside of regular park workers' hours (most Park staff work five days a week from 7-3) also helped -- nobody got in each other's way, or even had to look at each other.

Probably in the end an outdoor community bread oven in a public park is too small to prompt a union grievance. Many of the city's unionized workers are either very busy with bigger things, or very tired of working and mostly thinking about when they can go home, or very cynical about bureaucracy and secretly (or openly) happy to see something unusual, something unorthodox, in a park. In gratitude for their acceptance of our project's irregularities, for the first few years we always made sure to offer any passing park worker bread or pizza when the oven is going. They liked to see how it works. Curiosity trumps strict regulation, when the stakes are not too high.

Building regulations and fire regulations

When we bought our oven plans from Alan Scott we showed them to a city building inspector who had been a bricklayer by trade. He said the plans looked good, and he also told us that the oven was too small to come under the building code. So we didn't need a building permit.

The fire department's safety chief said that since the wood fire to heat the oven would be inside the oven chamber, the fire would not be an "open fire" with the associated fire safety issues. In addition, this oven would be 40 meters away from the nearest building (our rink change-house) and therefore it would pose no fire danger to another building. We also decided to build it only two meters from a water outlet. And except for the roof framing, which would be made of wood, all building materials would be fireproof.

The fact is, there's so much fireproof insulation around these ovens (inside the roof and wall cavities) that even when such an oven is over 800 degrees Fahrenheit inside, the outside walls and roof are hardly warm at all.

Printer friendly version

Printer friendly version